About

CV

2020

Paired interactions, Art square gallery, St. Petersburg, Russia

Group exhibitions

2024

Autumn Salon, Art Palace, Minsk, Belarus

𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘌𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘩 𝘐𝘴 𝘉𝘭𝘦𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘞𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘏𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘰𝘳𝘺, curated by Dzina Danilovich, National Center for

2023

2022

100 artists bringing figures to life, ARTIT book

Writings

Text by Nicholas Cueva for Peer Review Volume 1

“I once found a dead cat by the side of the road that had been lying there all day,” Katya waxed to me. “I buried him the next day.”

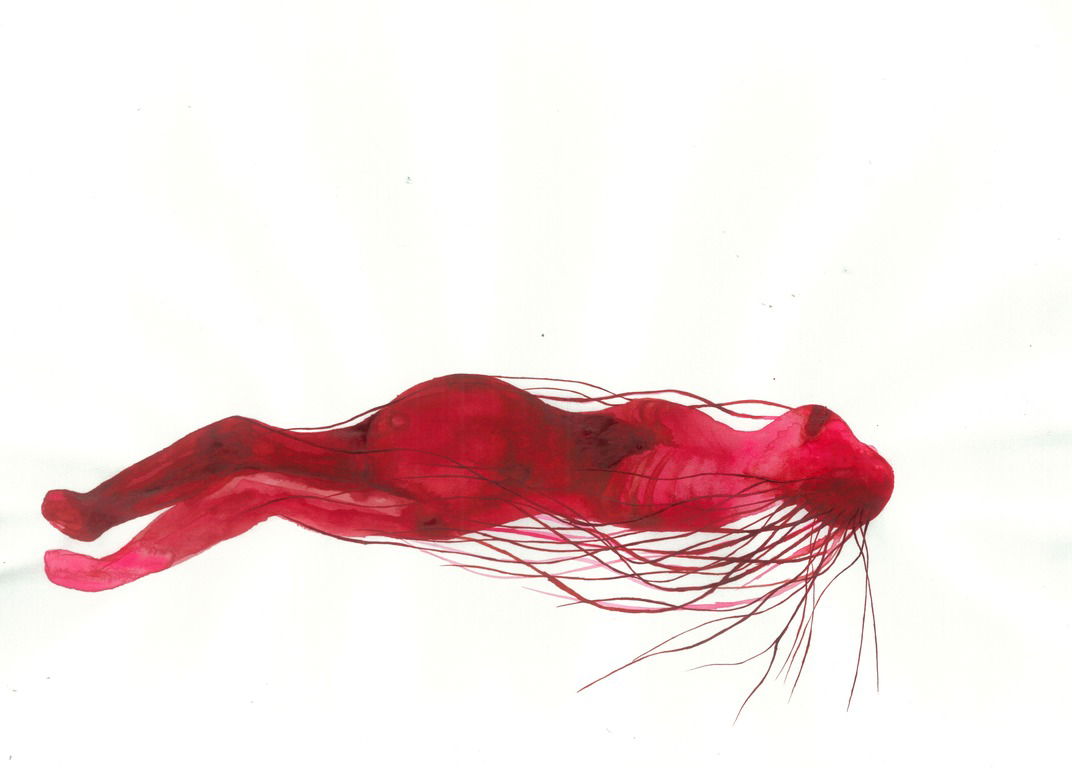

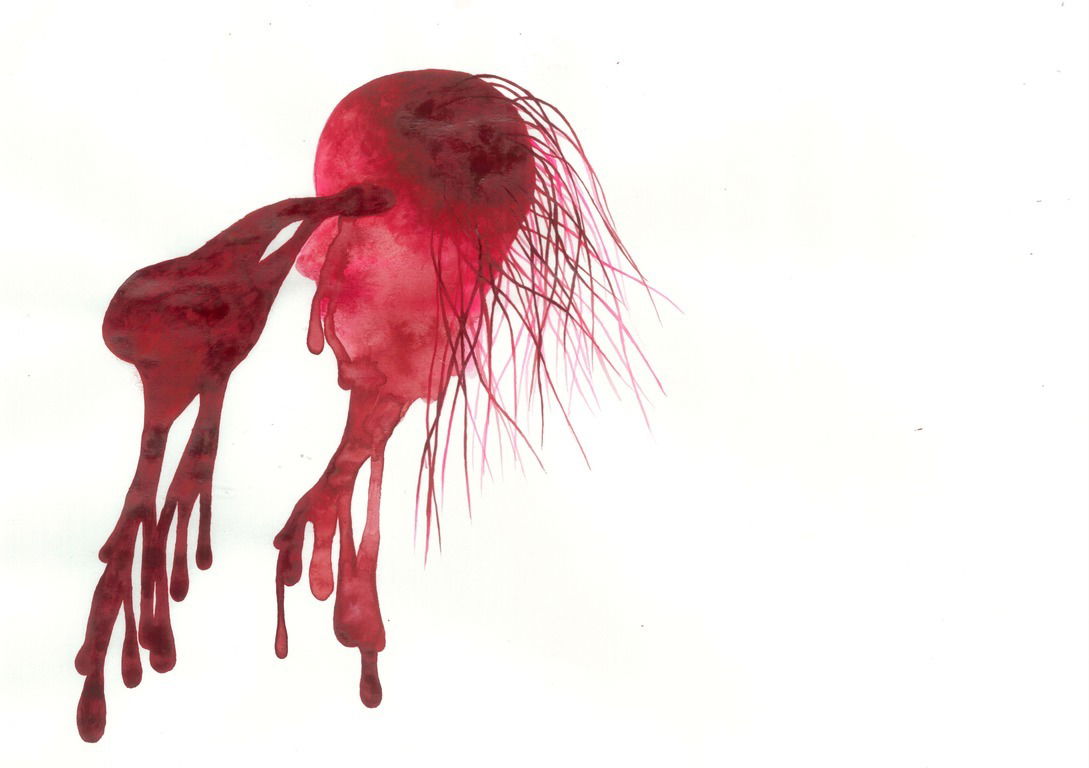

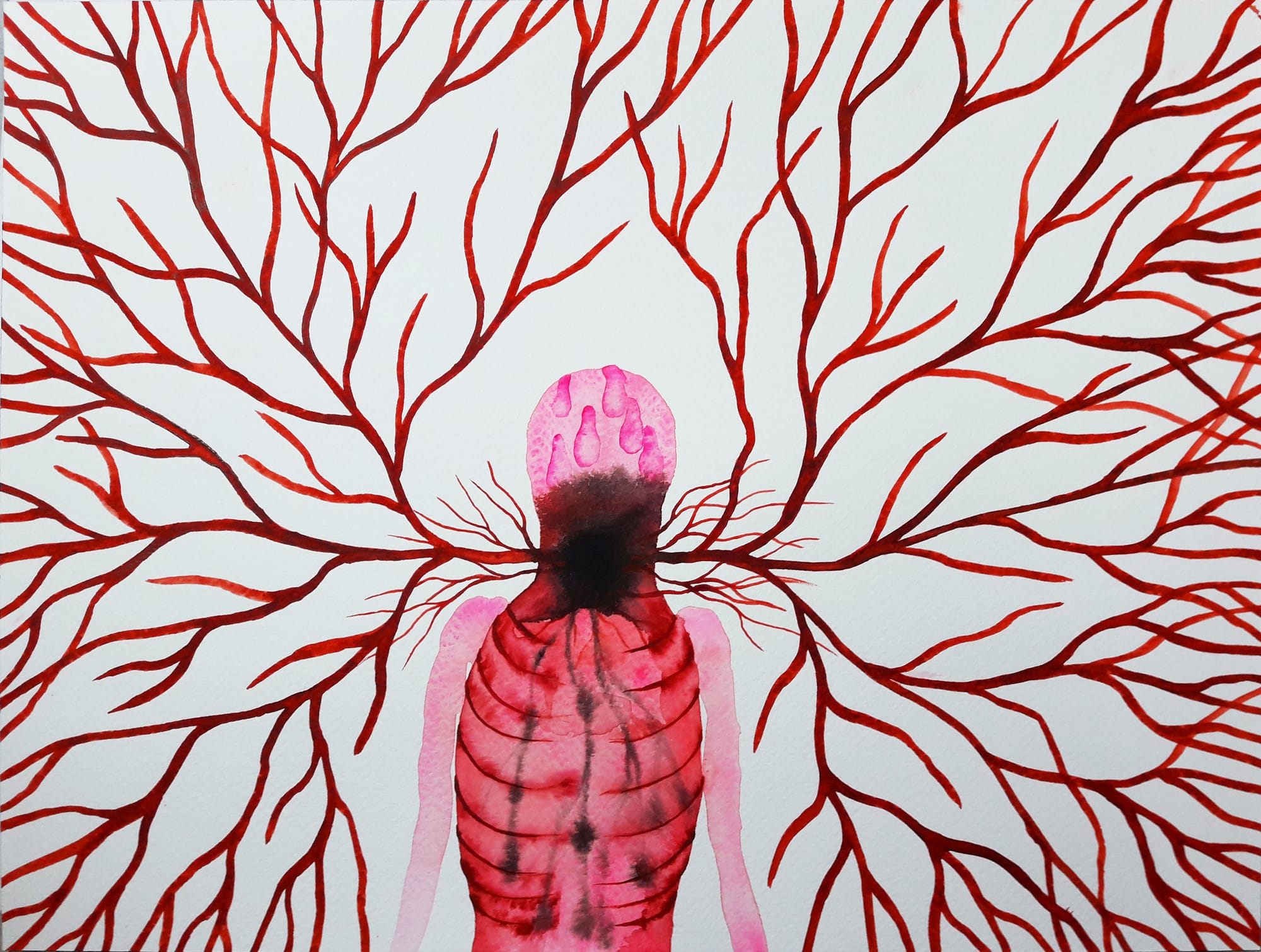

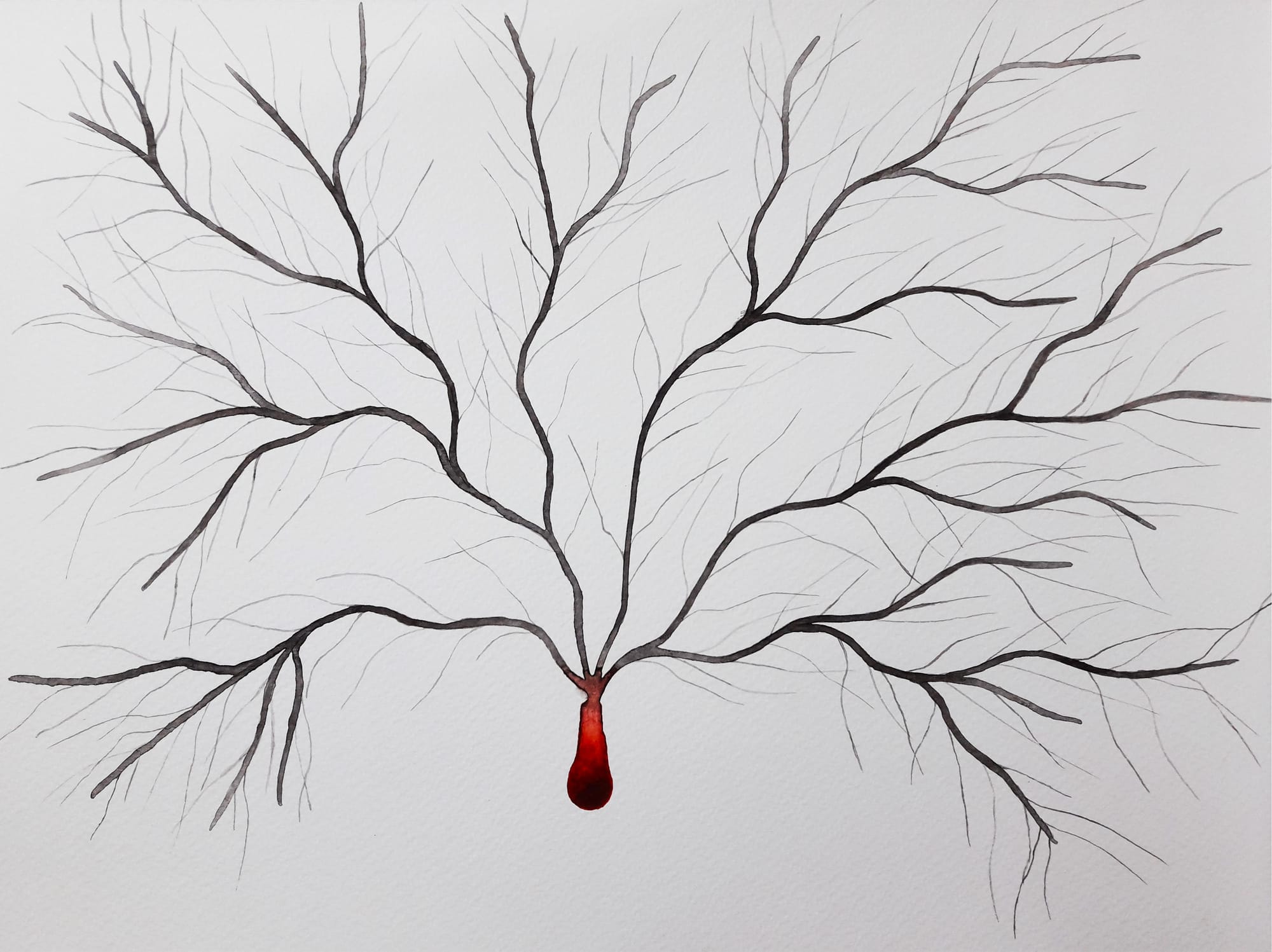

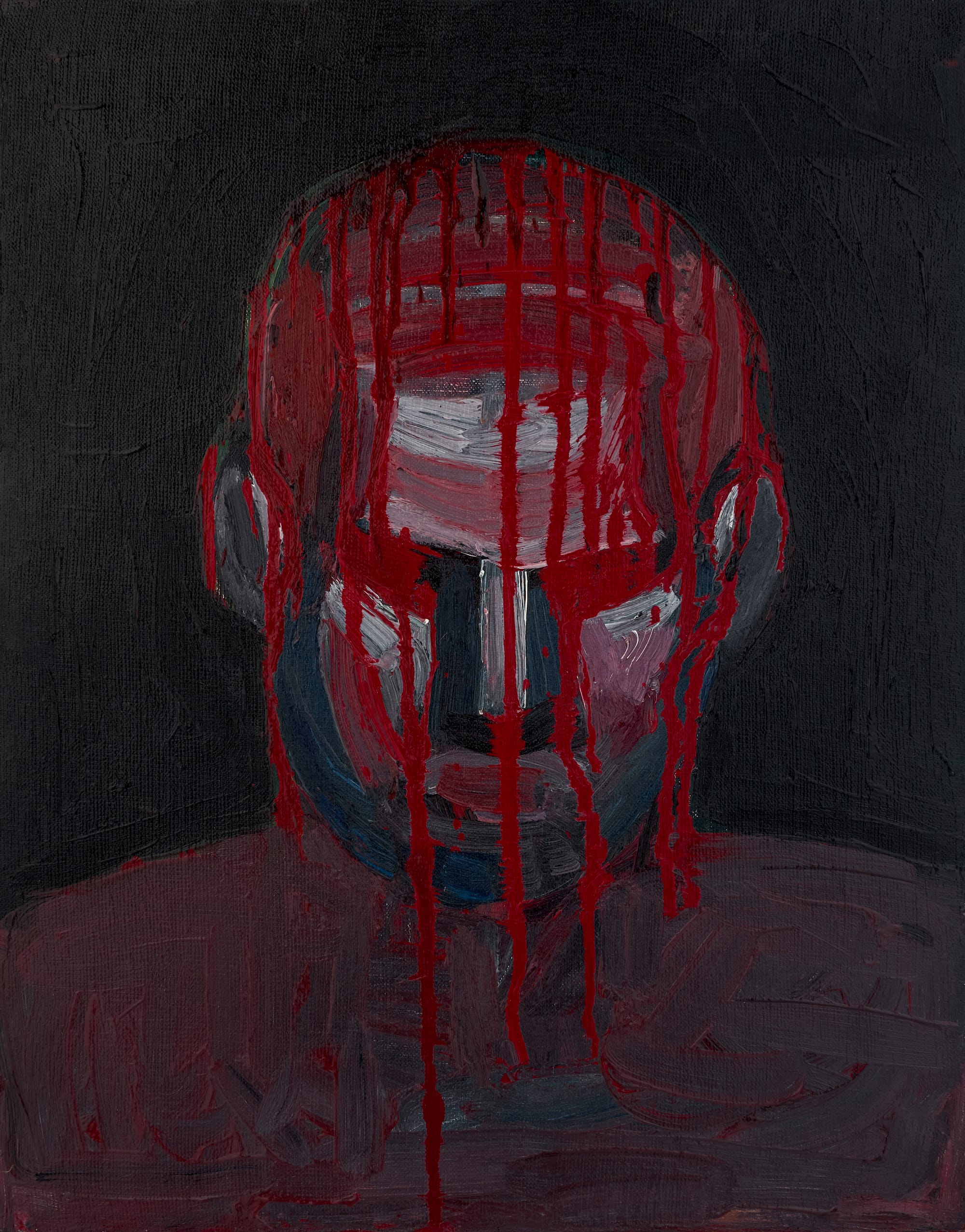

Katya Tishkevich’s work presents disgust, dark delight, and pathos with a cold hand akin to Marlene Dumas, disinterested brushwork with almost a holding back of violence. The type of empathy she makes available, high-octane and heady, is a little haunting. Her palette is closer to Louise Bourgeois’s spare watercolor musings, not straying too much from monochrome, in a severe way.

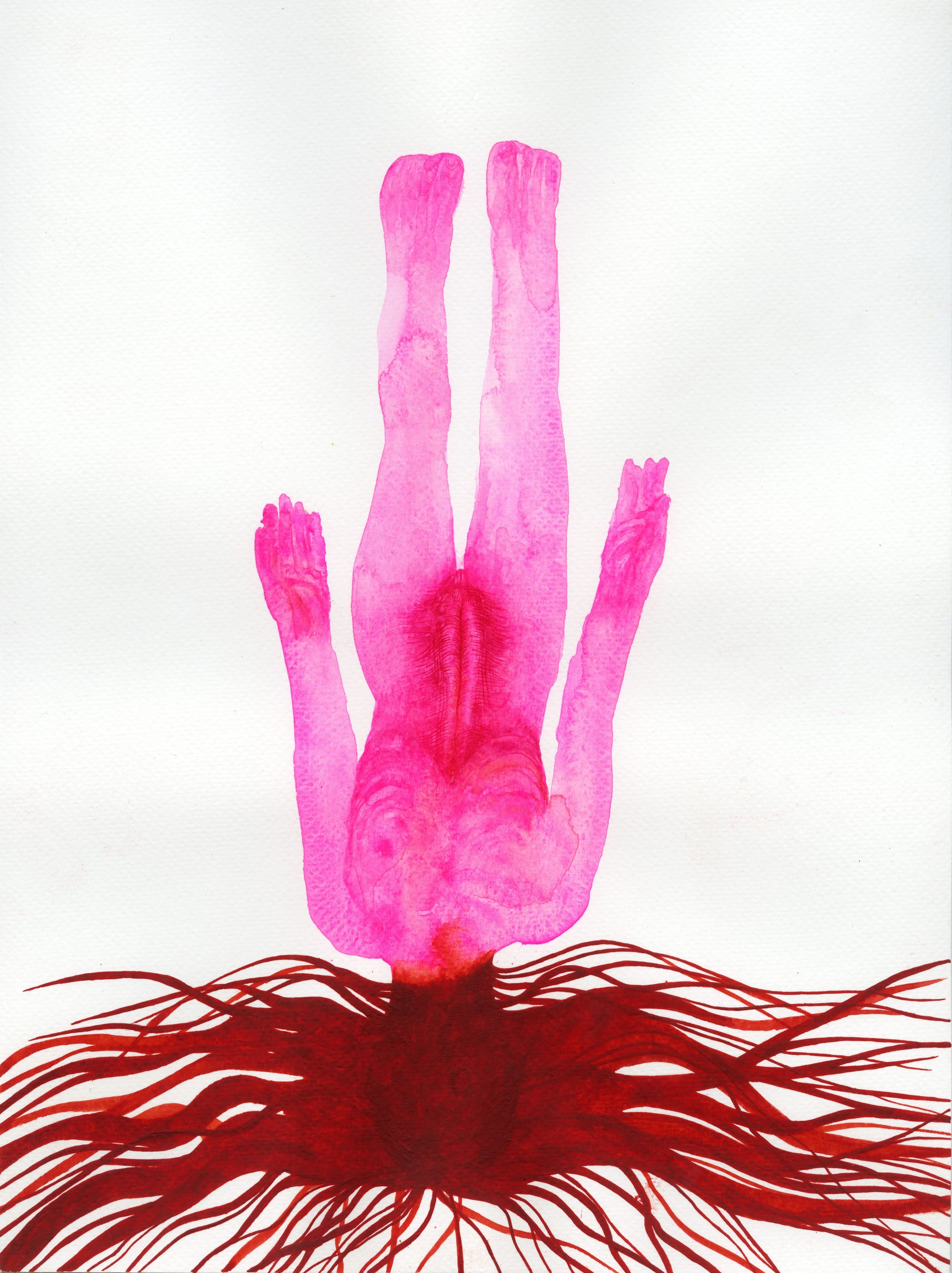

I see struggle and an uneasy knowing in Katya’s works. An unpaid karmic debt of sorrow, unable to be changed, focused into vignettes. It is the skeleton of hope left to freeze. Illustrations of final moments and portraits of regret.

Katya’s present pieces, with the stark relationship between marks and the forms they encompass, give her figures an alien feeling. In her watercolors, the body is laid bare with an analytic eye, its internal secrets and sinew pulled out and spread for the viewer’s consideration. In her oil creations, there is more weight in the marks, portraits seem blurry with the same anger and sadness that the depicted faces carry.

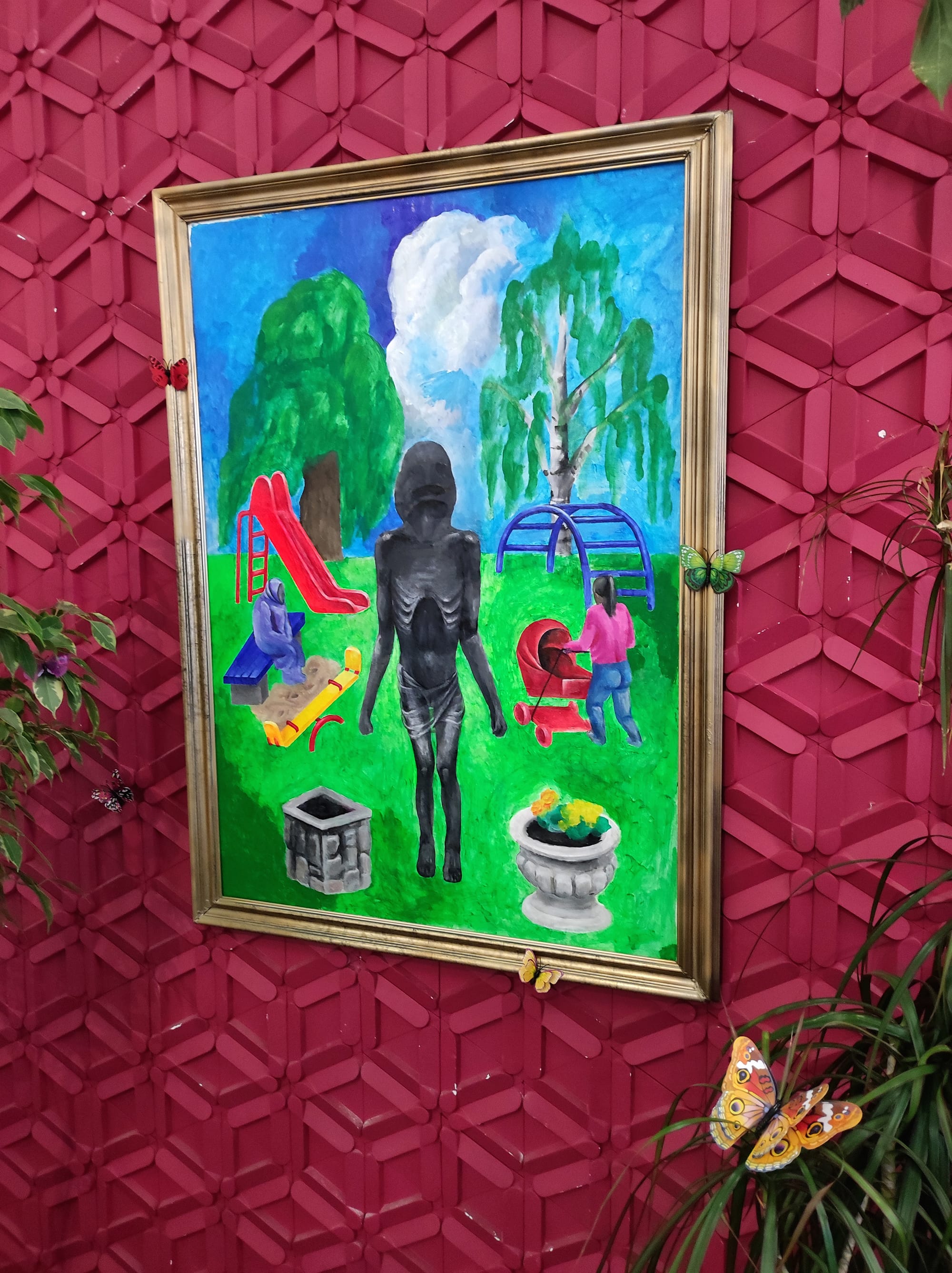

Her more figurative works often have skeletal thin bodies strewn about like pro-life propaganda. An aura of repugnance confronts the viewer, a specter of self-examination. There is something of the sensation we get from Mulholland Drive, the scene where a man describes a nightmare that unfolds exactly like the moment he is experiencing. He recalls seeing something terrible, just behind the building. Slowly, his elaborating and narrating march him forward into his dread, to fulfill his own prophetic vision, to meet his own terror.

Katya gives us moments to reflect on our own fragile existence, the miracle of life and the miracle of love, by showing us their limits and absences.

She often places central figures and forms in simple and solid backgrounds, further reiterating a clinical consideration, alienating and dehumanizing. This composition sets up a deeply charged focus on the by product of violence implied by her forms. The lifeless body doesn’t belong to anyone anymore, strewn like trash across a road; it is now a matter of image and metaphor, waiting for the viewer to gather it all back up again.

Her rare works with multiple figures feel somewhat like Leon Golub’s detached examinations of violence, with a haunting twist. Violence isn’t being carried out at the moment, per se, but its effects aren’t being addressed either: a passive form of post-torture torture. A huddled, naked, and injured man surrounded by cloaked figures actively ignoring him. Neglect, either through fear or apathy, barricades the relationships between figures, in opposition to the empathy teased out of the viewer. It is the story of the good Samaritan, without the Samaritan.

Her sculptures often reference burials, with bodies in rubble, forms like grave markers demarcating space among chaos, dead plants, soil. When I asked her about the possibility of life after death, she said, “I couldn’t even imagine something beyond the decay.” I suspect that’s not from a lack of imagination, but from her overwhelming sense of the chaos around her. Her portraits often have the sympathy of the sternly painted faces of Rouault: half-shadowed, half-abstract expressions framed with dark and direct brushwork.

Many of her figures are so eviscerated and abstracted that recognition of a person seems almost beyond us.

Stiff brushwork like a slap. Haunted.

“My favorite purpose of art is to provoke, disturb, force people to think, empathize, and develop empathy.”

She talks about Albert Camus’s The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus. Alienation, revisited in a post-Disney world.

The poverty of color and reliance on reds echo her post-Soviet background. Sparse, economical mark-making, for the highest emotional return. When asked about her color choices, she remarked, “They deeply agitate me. While working with these colors they echo my emotions, such as anger, pain, passion, struggle.”

She lives near the beginning of possibly the “last war,” in the way they meant it during the first world war: the “war to end all wars,” the eruption of which threatens all. This brief peace and order we have all come to take for granted, now seemingly paper thin, stretched like Katya’s figures.

Paying deep attention to negative emotions is rewarding (a sentiment that seems alien to the American mind).

We must imagine Katya happy. Returning over and over to the viscera and violence. Like Sisyphus pushing the rock, Katya puts a strong brush up against a nightmare and pushes back. There’s literature supporting the practice of returning to the image of trauma in an informed and controlled way, to alleviate the stress of memories. Can we empathize? Do we squeeze into the surgeon’s theater? Does the execution chamber have another seat? Do we stop to give change to the man holding up his sunken face? Can we look in the mirror one more day?